At 9,500 feet in the Snowy Range Mountains, two old men are building a cabin that is off grid, out of cellphone range, and deep into black bear territory.

On the one hand, it is simple to understand their motivation.

The intoxicating scent of spruce lingers in the air. Brook trout jump for flies in the nearby Medicine Bow River, and pine-clad peaks rise in all directions, giving the impression that you’re being cradled in a pair of massive hands.

But that doesn’t explain why these old-timers believe they can handle the task.

Keeping busy in retirement is essential for maintaining a healthy body and sharp mind. However, this enterprise appears to be designed to destroy what remains of their bodies, raising the question of whether their minds have already gone to seed.

“We’ve worked like dogs to get to this point,” said Dave Simpson, 74, one half of this dubious undertaking, wiping sweat from his brow as he sat down on a cinder block stool to rest.

There’s plenty of reasons why he feels this way.

Consider that every scrap of material must be hauled in on a ridiculous U.S. Forest Service road that jostles your organs like balls in a bingo tumbler.

Consider that, in addition to being on a budget, road access limits the resources and tools available for the job, resulting in additional physical work.

Finally, consider Simpson and his compatriot’s combined age of 148 years. With this project still in its early stages, they may believe that working dogs have it easy by the end.

Nonetheless, they toil under the scorching July sun, digging out boulders and constructing sandwich beams from their limited supply of dimensional lumber. The expressions on their sunburned faces indicate that they, too, wonder if the juice is worth the squeeze.

The truth is that this cabin is much more than just a getaway. Rather, it is motivated by loyalty and honoring a promise made 44 years ago.

Meet The Guys

Larry Ash, 74, is a former Air Force reservist and retired computer engineer. He has glossy gray hair and a pair of unruly eyebrows with jutting strands like frayed electrical wire.

He has a strategic mindset that leans slightly toward paranoia. He’s the type of person who might begin a sentence with, “If I were a terrorist…”

In the early 2000s, he threatened to quit his job as computer systems manager at the Casper Star-Tribune after the publisher announced plans to partition the office.

His reasoning was that in the event of a terrorist attack, the partitions would direct too many people out the same exits, allowing snipers outside to easily pick them off.

“I told them, ‘If I were a terrorist, I would love those partitions because I’ve got a kill zone built in,'” he told me. “They thought it would keep [bad] people out, and it’s, like, ‘No, it just means that people running away can only go in a few directions.'”

True, but is that the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the words “office partitions?”

Although he may have been projecting, one of his most common statements is that all of life’s problems, including homeowner associations, can be easily solved with napalm.

The reason Ash is here with a nail gun today dates back to 1969. He was a business major at the University of Wyoming when he ran into a fellow student, Dave Simpson, who was sprawled in the dormitory hallway reading a book.

I literally stepped over him. “He was out there because his roommate had an early schedule,” Ash explained. “But he was from Chicago, and 9 o’clock was not the time you go to bed in Chicago.”

At the time, Ash couldn’t have imagined naming his own son after Simpson. He never imagined that 56 years later, as septuagenarians, they’d be working like dogs to fulfill their long-standing promise of having neighboring cabins in the woods.

Simpson

Dave Simpson has worked in the newspaper industry for nearly 50 years as a journalist, editor, and columnist.

He speaks with an impartial tone and a Midwest accent that hints at his Chicago upbringing. His close-set eyes and baby-round face give the impression of timid innocence, as if he were in a constant state of mild surprise.

Among his life’s surprises was the realization of how difficult it is to build a cabin.

As a transplant, he fell in love with Wyoming’s vast open spaces and abundance of outdoor activities. It came as no surprise that he wished for a cabin in the woods.

With this in mind, he purchased a plot of land in the Medicine Bow National Forest in 1981, a rare private holding resulting from a mining claim from the twentieth century.

Simpson and Ash, who lived in Casper at the time, met weekly at a local dive bar to work out napkin-back blueprints for a cabin based on designs from a DIY pioneer living series called the “Foxfire Volumes.”

The idea was simple: logs of downed timber laid crosswise and held together with crudely axed dovetail corner joints. Cement spackle fills the gaps. Wooden floors and a metal roof. When they had decided where they wanted the doors and windows, they simply sawed them out.

“Originally, we figured it would just be a place to get out of the rain,” said Simpson, who was surprised by how long this seemingly simple design took to build, working weekends throughout the summer and early fall. “We chose 14 feet by 14 feet because we assumed it was the largest log two guys could pick up. We didn’t have any heavy equipment, and I didn’t have much money.

“We stored logs for three years. Every Sunday afternoon, we drive back to Casper and say, “We’ve got to take a weekend off; this is just too hard.” But then Thursday rolled around, and we’d say, ‘Well, we better get back up there.'”

The construction has never really stopped.

The roof collapsed, so they added a loft. They had built an outhouse but were tired of the trek, so they added a bathroom, shower, and kitchen.

Repairs are always in progress, particularly after a black bear tore through side panels last winter in search of cooking spice.

“There are few friends who would work as hard on a project as Larry did. “Every log in my cabin, he was on one end and I was on the other,” Simpson explained.

Cabin Number Two

Ash had always planned to buy an adjacent property and build a second cabin there. Finally, 44 years later, last summer, the couple started work on cabin No. 2, which is only a stone’s throw away.

“They could not be more different. My cabin was pretty much planned on napkins at Frosties bar. “He has an incredible plan,” Simpson stated. “I’m repaying a debt. He helped me build my cabin, and now I am helping him build his.”

Simpson was diagnosed with prostate cancer just as the project was getting underway, casting doubt on its future.

After a successful prostatectomy, Simpson returned to work. Despite his limited physical abilities, Ash redesigned the structure from two to one story.

The Routine

Ash sleeps in the loft and rises with first light. He heads straight for the build site and mulls over the details of the day over in his mind. Simpson, meanwhile, cooks up a scramble and they discuss the day’s work ahead over breakfast.

“I model everything in my mind,” Ash explained. “I walk around here thinking about every board and piece and organize in my mind so I can keep the stupid mistakes to single digits each day.”

Even with a simple design, just picturing these two at work makes your back ache: hauling 30-pound bags of cement by hand, digging out boulders to place foundation piers, hoisting sheets of plywood above their heads.

The next step is to build and install trusses. They’d like to have trusses delivered, but as other cabin owners in the area have discovered, you can have a large truck bring in a truss, but you’ll have to pay another truck to come in and haul the first truck out.

Ash accepts the hardship as a necessary part of his own survival.

“If you simply sit in a rocking chair, someone will eventually come find you…” “And you’ve expired,” Ash said. “You need to keep your head and body moving. “This has been a lot of head and body.”

Of course, there is a time and place for rocking chairs.

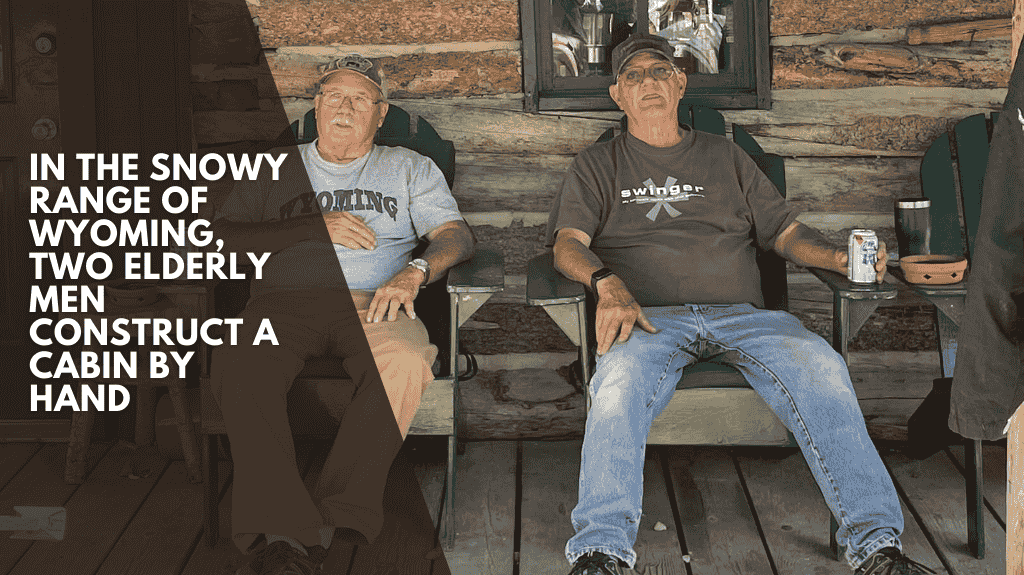

At the end of the day, Simpson and Ash walk back to cabin No. 1, crack beers, and collapse into a pair of rocking chairs.

They occasionally sit and listen to cassette tapes of Prairie Home Companion. Other times, they will select a book from the bookshelf. Today, they stare out at the forest and engage this reporter in conversation about property taxes and other annoyances that could be resolved with napalm.

While you may wonder if septuagenarians are wise to embark on such a difficult project, the image of these two lifelong friends rocking side by side after a long day’s work appears to justify their efforts, whether they survive or not.

“In your 70s, it’s one blasted thing — ailment, test, procedure, surgery — after another,” Simpson wrote in a recent Cowboy State Daily column. “You might be young at heart, but these are your high-mileage years.”

Perhaps because of the construction of this second cabin, the high-mileage times ahead will feel especially accelerated, as if he is aging in dog years.