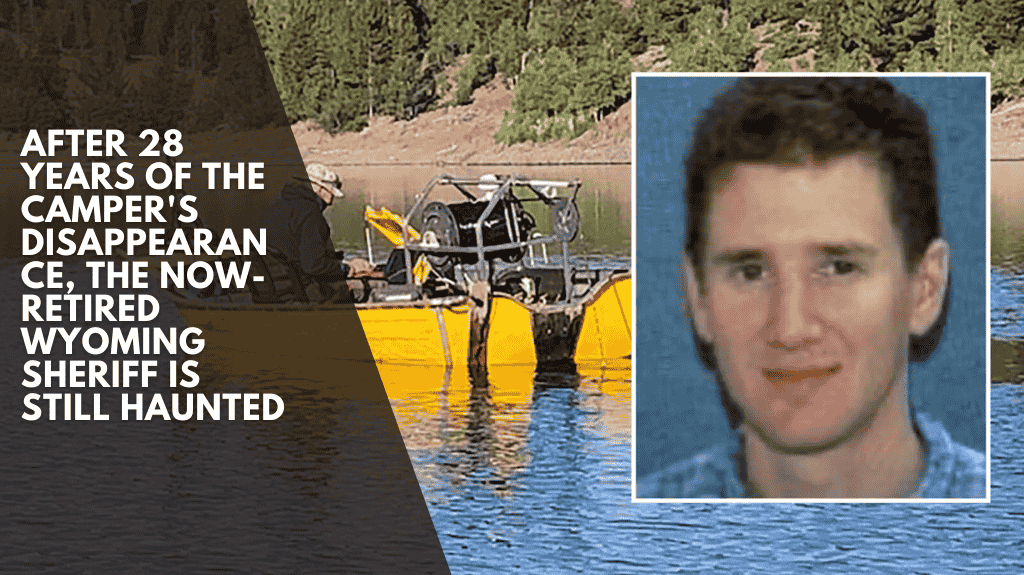

It has been nearly three decades since a 27-year-old Maryland man went missing in the Wyoming mountains while on a weeklong camping and fishing trip with friends.

In late August 1997, David Crouch was camping in the Wind River Range and was last seen on the banks of Island Lake, holding a fishing rod.

Despite two weeks of intensive searches by the Sublette County Sheriff’s Office and approximately 50 local search and rescue volunteers who combed miles of rocky and forested terrain with dog teams, horses, and helicopters, no trace of Crouch was ever discovered.

Sublette County Sheriff Hank Ruland was the lead investigator in the search for Crouch, and he still remembers it vividly nearly 30 years later.

Ruland, a four-term sheriff who retired in 2005, said Crouch’s disappearance has haunted him as the mystery continues. During his tenure, he frequently searched for missing hikers and campers in the mountains.

The difference is that they are usually discovered within a day or two, but not in Crouch.

“We tried everything,” Ruland explained. “It’s the ones you don’t find that really bother you.”

Need to explore

Crouch had traveled from Maryland to Wyoming to fish and camp with three friends.

The group had hired Terry Pollard of Bald Mountain Outfitters, a Pinedale outfitter, to take them on horseback for a week of camping and fishing in western Wyoming’s Wind River Range.

Pollard did not respond to a request for comment, but he did tell the Baltimore Sun in 1997 that Crouch couldn’t sit still and wanted to explore the wilderness.

Crouch, despite being an avid cyclist, sailor, and runner, reportedly had little experience camping in the wild, according to an acquaintance quoted in the Baltimore Sun article. As a result, he “was charged up for the Wyoming journey,” according to his acquaintance.

Crouch struggled to sit still, despite repeated reminders from Pollard and his group that they had a full week to explore.

According to media reports, they warned Crouch several times that they all needed to stick together for safety reasons.

“It’s beautiful, pristine country, but it’s also really wild and rough,” Ruland told Cowboy State Daily.

Last known sighting

According to the Baltimore Sun, the group agreed the night before Crouch disappeared to travel from their campsite a few miles to Island Lake on Sunday, where they planned to fish before meeting for lunch at the nearby Fremont Crossing trail junction at 2 p.m.

After arriving at the lake, Crouch was last seen fishing on the west side around noon. Crouch was not present when that person looked for him later, and he did not show up for their scheduled lunch.

Initially, the group was not concerned. It was a busy Labor Day weekend full of hikers and campers, and they assumed he would be safe as long as he stayed on the trails. However, when he still did not appear hours later, they contacted law enforcement.

Potential sighting

Despite the large number of people in the area that weekend, only one group of hikers reported seeing someone who matched Crouch’s description, Ruland stated.

The group told Ruland that at around 7 p.m., they saw a man in a red and black flannel shirt carrying a fishing pole on a trail several miles to the north and east of where Crouch was last seen.

They had said “hello” to him, but he walked away without responding.

Ruland stated that without positive confirmation, it is impossible to determine whether that was Crouch. If it was him, he had wandered quite a distance, Ruland stated.

According to “Lost Person,” people who are lost in the woods consistently go uphill.

Of those lost hikers, 32% to 48% climb uphill from their last point of reference in search of a better view or cell signal.

Koester discovered that uninjured hikers lost in the wilderness have a 97% survival rate if found within 24 hours. However, the chances of survival begin to dwindle at 96 hours or more, with lost hikers having only a 49% chance of surviving the elements.

Then there’s the weather, which was unfavorable to Crouch on that late August weekend. Not only was it a moonless night with limited visibility, but the temperatures had dropped into the 30s the night he vanished. News reports indicate that they continued to drop in the following days, accompanied by light snowfall.

Crouch was not prepared to withstand the cold weather or rough terrain.

He was dressed only in jeans, a plaid flannel, and hiking boots and lacked all of the necessary survival gear, such as a tent, sleeping bag, water, snacks, compass, matches, and anything else that would help him survive a night out in the cold.

He was woefully unprepared, Ruland said.

Family Flies To Wyoming To Help Search

Efforts to reach members of Crouch’s family in Stevensville, Maryland, were unsuccessful, but they have not spoken much about the case over the years. In 1997, the Baltimore Sun said they declined to be interviewed and asked those who had been on the trip with him to do the same.

Crouch was described as an avid runner and cyclist who managed a Stevensville bike store who was married for three years to his high school sweetheart.

Ruland remembers the family flying out as search efforts continued and said they were very polite and helpful and understood the arduousness of the efforts at hand as soon as they saw the difficulty of the terrain and what the searchers were up against.

To date, other than that one potential sighting by the hikers, no trace of Crouch or his fishing pole have been located in the decades since he disappeared.

Best Guesses And Speculation

In the absence of answers, searchers like Ruland were left to speculate what might have happened to Crouch based on his last known location and their own theories and speculation.

If Ruland was a betting man, he would guess that Crouch may have tried to take a short-cut back to their base camp and crossed an inlet above the lake and tripped and fell on the slippery rocks.

The shock of the cold water at the lake at above 9,000 feet would have been jarring to Crouch’s system, potentially causing him to drown with fishing pole in hand.

This theory gained a bit more credence in his mind when a couple years later he and his then-undersheriff helicoptered a couple cadaver dogs into that area, where the dogs alerted on the shore of the lake where Ruland thinks Crouch may have fallen in.

It’s still just a guess, Ruland acknowledged, but the lake was not searched at the time he disappeared.

Better Equipment

Back then, conducting a water search for Crouch would have been difficult given their limited technology at the time and the logistics of getting a search team and boat to the lake had there been credible evidence to suggest he’d fallen in, says John Linn, leader of the underwater team for Tip Top Search and Rescue (TTSAR), a volunteer group that works under the auspices of the Sublette County Sherriff’s Office.

Over the past 30 years, underwater search and rescue technology has improved greatly, and they seldom – if ever – put divers down in high-elevation mountain lakes given the associated risks at high altitudes, he said.

Linn, who has been with the group since 1985, said that today TTSAR uses more advanced technology, including a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) equipped with cameras and a claw as well as a $60,000 side-scan sonar used to locate people, vehicles or boats and other objects under water.

The scanner uses sonar technology that sends out signals that reflect off objects underwater and creates visible shadows and images that the team then analyzes to see if further investigation is needed. If so, the team marks that spot and sends the ROV, which is about the size of a carry-on suitcase, down into the water with live front and back cameras and a grasping claw to latch on to the person or object.

“We have the capability to go 500 feet deep, and it only takes a small generator to run it,” he said. “And you never risk anybody’s life with that robot.”

The TTSAR underwater team is the only one in the state with these particular capabilities and has conducted dozens of missions in Wyoming and surrounding states, Linn said, estimating they have recovered between 15 to 20 victims to date with these advanced tools.

The tricky part of high-mountain lake rescues – both then and now – is getting the equipment to the scene, which requires either being driven in or airlifted by helicopter, including their boats and search crew.

These efforts can be significant, Linn noted, and in Crouch’s case, would also require the permission of the U.S. Forest Service as well as funding to bankroll the extensive operation. They also work solely under the directive of the Sublette County Sheriff’s Office, so likely there would have to be new credible new evidence to get the okay to go in, Linn said.

They’ve worked on cold cases at the request of DCI and other agencies in the past, he said, but the request needs to come from law enforcement.

“It wouldn’t be an active search like we normally do,” Linn said.

In the meantime, Crouch’s disappearance remains a mystery.

Into The Wilderness

Crouch is not the only person who has gone missing in the mountains while under Ruland’s watch, but he is the only one who has yet to be found.

George Clock went missing in the Wind River Mountain area in 1994, in one of Ruland’s most perplexing cases.

Clock, a 44-year-old robotics engineer from Sacramento, California, was residing in Riverton at the time. According to the Casper-Star Tribune, he had told friends that he planned to backpack in the Green River Lakes area and possibly scale Gannett Peak.

After his hike, Clock planned to meet friends on the East Coast. When he didn’t show up, his family reported him missing on November 3.

A month later, a group of hunters discovered Clock’s abandoned vehicle hidden in the bushes on Moose Gypsum Road near Green River Lake, about 50 miles north of Pinedale, with the license plates and vehicle identification number removed. However, authorities discovered a second VIN on the vehicle, tying it to Clock.

A few months later, a hiker discovered the license plates, which had been hidden in the same brush.

The hidden car and missing plates indicated to Ruland that Clock was either a victim of foul play or had deliberately vanished on his own.

Ruland believes Clock may have intentionally disappeared and was inspired by Christopher McCandless, who, like Clock, abandoned his car and removed the license plates before disappearing into the Alaskan bush in 1992 with the intention of living off the land.

McCandless did not last long. About four months later, a moose hunter discovered his remains on an abandoned bus, having starved to death.

Jon Krakauer, an outdoor writer, wrote about McCandless in a January 1993 article for Outside magazine. He later expanded it into a best-selling book titled “Into the Wild,” which was made into a film in 2007.

Given the timing of the first article, Ruland believes Clock may have read it and been inspired to face the elements and go off the grid.

Despite the similarities in the two men’s stories, Ruland believes there is no way to know what his intentions were or if he truly wandered off on his own.

Regardless, given the time of year, Ruland stated that the odds were stacked against his survival.

“That’s kind of like committing a natural suicide when you go up and challenge the high country in October when a storm is coming,” he told me.

Clock’s remains, like McCandless’, were discovered when a hiker came across a partial skull north of the Green River trailhead about a year after he went missing.

His abandoned campsite was also discovered near the skull, along with Clock’s backpack, which contained keys to his abandoned vehicle, a knit cap, sleeping bag, and other outdoor gear.

It took authorities two decades to positively identify the skull as Clock in 2016, after two previous “inconclusive” lab results, thanks to advanced DNA technology.

Other Missing People

Along with Crouch and Olson, four other Sublette County residents.

This includes Tracy Jensen, who went missing in February 1999 at the age of 23, according to the Wyoming Department of Criminal Investigation’s missing persons database. There is little information available about how he went missing or the circumstances surrounding his case.

Vanessa Sue Omen is also missing; she was last seen with her boyfriend in a red jeep outside the LaBarge post office on March 1, 2016.

Lynn Dianne Olson, then 16, went missing on June 28, 1963, while visiting her grandparents’ dude ranch in Green River Lakes.

She and her twin brother, Mike, grew up in the neighborhood but later relocated to Salt Lake City with their mother.

Mike, who was also visiting Wyoming with his sister, told authorities that he last saw her crossing a footbridge at the end of one of the lakes.

Search teams combed the area and dragged the lake where she was last seen.

Then, strangely, her clothing was discovered about a week later, neatly stacked and folded on a rock near the lake in an already searched area, about 200 yards from the shore.

This prompted authorities to drag the lake again, with no results, and to bring in divers from Cheyenne to search the water, a move Ruland described as extraordinary for law enforcement at the time.

Still, no trace of her was discovered, nor was any evidence recovered. Aside from a few reported sightings in southwest Wyoming and Utah over the years that did not pan out, there have been no recent developments.

Ruland, who was the same age as Olson and her brother at the time, said the mystery has haunted him ever since.

“It was always in the back of my mind,” he told me.

He laments the lack of crime scene tools and technologies in the early 1960s, but says the sheriff enlisted the FBI’s help. Later, when he became sheriff, he looked through the old files and discovered Olson’s case. He discovered a letter to the then-sheriff from former FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, who promised to send out a couple of agents to help.

“They did a pretty good job,” he explained. But, after decades, there are no new clues or evidence.

Ruland had nothing to work with.

These are the lingering mysteries that haunt the retired sheriff, but he believes it’s never too late.