Chris Kirol, a wildlife ecologist, has recently spent time surveying what were once some of the Powder River Basin’s largest sagebrush tracts.

The veteran researcher has been looking for native vegetation such as sagebrush, as well as the chalk-colored cylindrical droppings that indicate where one of the biome’s icons, sage grouse, has spent their time.

On a Friday afternoon survey, Kirol received a call from WyoFile and described the landscape all around him, which had been completely transformed for the worse.

“It’s almost completely dominated by cheatgrass and Japanese brome,” Kirol stated, referring to two noxious, nonnative grasses.

“I haven’t found a single sage grouse scat,” he explained, “which is expected because there’s about five sagebrush left in this quarter-mile area.”

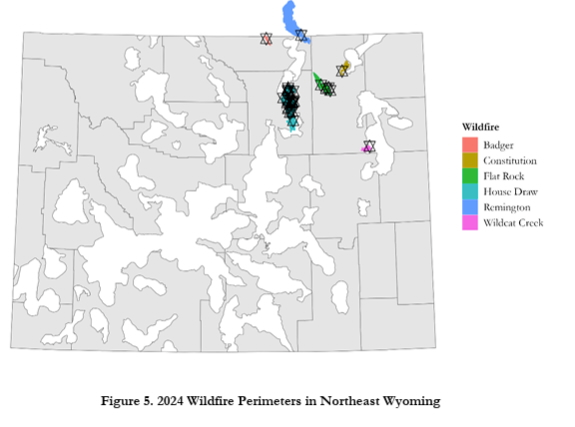

Kirol was walking through a burn scar left by the House Draw Fire, which burned nearly 180,000 acres. The Johnson County fire, which ripped through grassland and shrubland in August 2024, destroyed more than 100,000 acres of “core” sage grouse habitat in northeastern Wyoming, where the birds live — more than a third of the best habitat in a region where the population was already struggling. The House Draw Fire’s perimeter included 20 sage grouse breeding grounds, or open areas known as leks.

“They were large leks,” Kirol said. “We know from years and years of research that this was one of the areas with the highest density of sage grouse left in northeast Wyoming.”

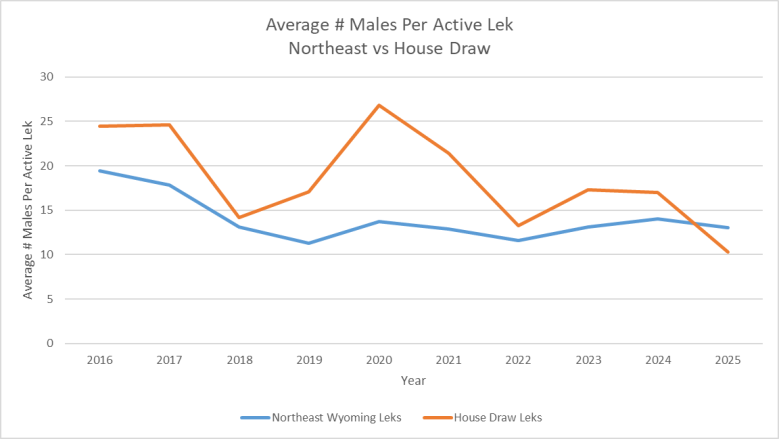

Male sage grouse were observed displaying at eight of the twenty leks in the first year of post-fire monitoring, which was the same as during pre-fire surveys in 2024. However, the tallies in the burn scar tumbled.

“Those leks were down 40%,” said Nyssa Whitford, a sage grouse/sagebrush biologist with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department.

“Those birds took a hit, there’s no question about it,” she told me. “If you see the House Draw Fire on the ground, you’ll understand why it’s down. It burned hot and fast, and in many places there isn’t much [sagebrush] left.”

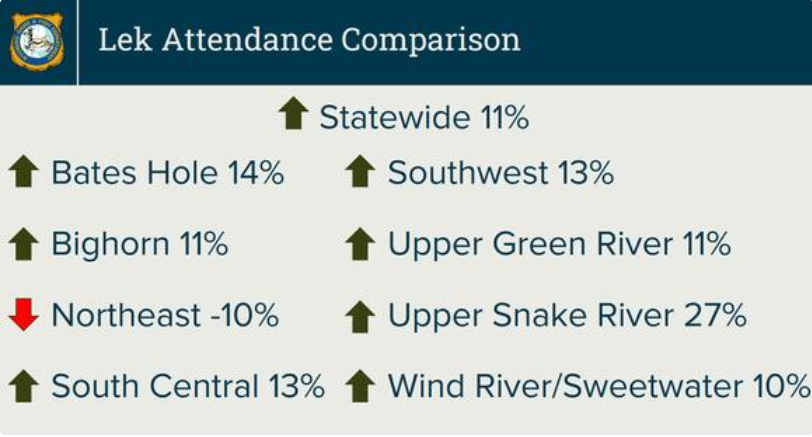

The House Draw Fire’s negative effects help explain why counts at the 336 occupied sage grouse leks in northeast Wyoming fell by 10% in 2025, despite the fact that the naturally cyclic species performed well across the Equality State overall.

Near the peak

In the spring of 2025, hundreds of biologists, wardens, and volunteers surveyed Wyoming’s sagebrush-steppe and found more than 30,000 male sage grouse strutting on 971 of the state’s known, occupied leks.

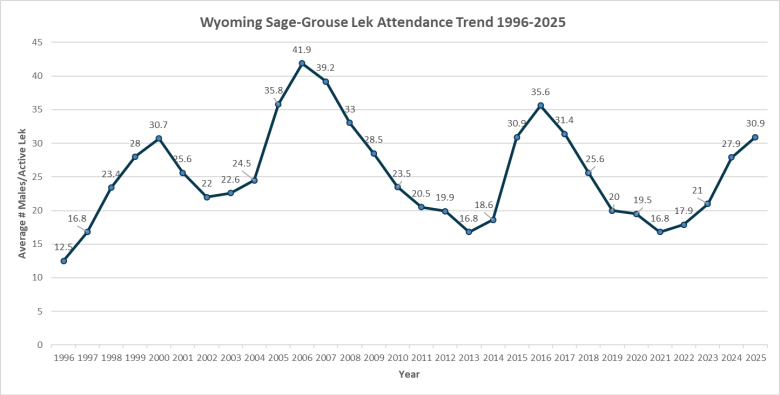

That translates to an average of 30.9 birds per active lek, a 10% increase over 2024 counts and nearly a doubling of the population since the previous low point in 2021.

Those swings are normal and part of the sage grouse biology. According to Whitford, it takes an average of 9.6 years to complete a cycle across Wyoming.

“If I look back at the past data, I feel like this year is the peak,” says Whitford. “But we won’t know that until next year.”

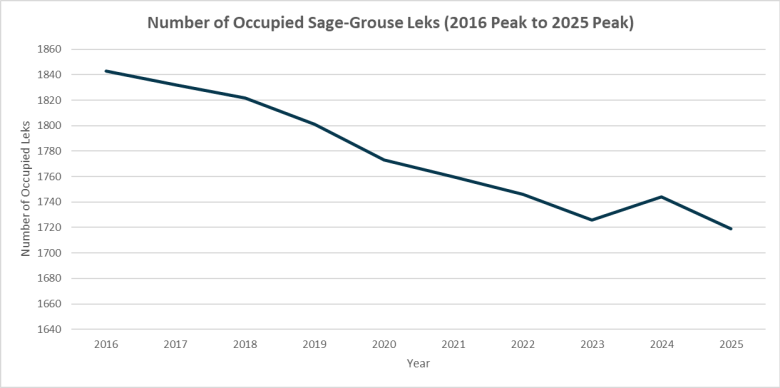

Lek counts peaked in 2016, with 35.6 birds tallied per active lek, according to Game and Fish statistics. Previously, the average lek had nearly 42 strutting males. If 2025 is the next peak, sage grouse abundance will have declined by nearly 36% since 2006.

Whitford noted that in 1999, there was a lower peak of 30.7 birds per lek.

Other metrics indicate that the state’s population continues to decline over time. Since the 2016 peak, the number of occupied leks statewide has decreased by about 6.5%, from approximately 1,840 to 1,720, according to Game and Fish data.

Sage grouse rely on a biome called sagebrush-steppe, which is disappearing and degrading at a rate of 1.3 million acres per year in western North America.

According to a 2021 U.S. Geological Survey report, sage grouse populations have declined by an average of 3% per year over the last half-century due to ongoing habitat loss.

For more than three decades, the chicken-sized bird’s persistent struggles have prompted petitions for Endangered Species Act protections, but voluntary state plans have prevented the US Fish and Wildlife Service from listing it, most recently in 2015.

Wyoming has the world’s largest and best sage grouse habitat, with approximately 38% of the remaining birds. The 2025 lek count increased by double-digit percentage points across almost the entire state.

Uniquely struggling

The only exception was northeast Wyoming, where counts fell by 10%. While the House Draw Fire was a factor, the outlier datapoint could also be attributed to the region’s shorter natural cycle duration, according to Whitford.

The number of males observed per active lek in northeast Wyoming was 13, which was less than half of the statewide average. The population performance in the region has consistently been the worst in Wyoming.

“Northeast Wyoming has always been at the edge of sage grouse range,” Whitford informed the audience. “The habitat is unlike the rest of the state. It runs a little drier and easily converts to grassland.

Wyoming’s conservation plan for the northeastern sage grouse, which was last updated in 2014, describes a long-term decline in habitat and species. According to the report, the “patch size” of sagebrush cover in the Powder River Basin has decreased by more than 63% over the last 40 years, from 820 acres to fewer than 300. Overall, sagebrush cover in the watershed decreased 6% as a percentage of the landscape, from 41% to 35%.

Long-term data show that leks are being abandoned as their habitats degrade and disappear.

According to Wyoming’s most recent statewide sage grouse report, only 178 of the 606 documented leks in the northeast region were active during the 2024 breeding season, or roughly 29%.

“Average male lek attendance in northeast Wyoming has decreased significantly over time, decreasing by more than half in the last 30 years,” wrote Game and Fish Wildlife Biologist Erika Peckham, who authored the section of the report.

Northeastern Wyoming’s 2024 wildfires, particularly the House Draw Fire, are almost certain to exacerbate the declines. Although surveyors found male sage grouse at 40% of the leks in the House Draw Fire scar during the 2025 lek counts, the large interior leks near where all the sagebrush burned up are likely to vanish entirely.

“Females nest almost exclusively in sagebrush—99% of the time,” said Kirol, the Sheridan-based sage grouse biologist. “So if the females aren’t showing up anymore … there’s going to be no [population] recruitment to those leks.”

Male grouse may continue to display on their lekking grounds for the rest of their lives, he said, which could be another five years. However, they will eventually die out.

“I expect a lot of the leks in the interior will blink out,” Kirol told me. “I hope they don’t, but that’s what has been shown in the past.”

The smaller a sage grouse population, the more vulnerable it is to extinction. That’s what happened recently in North Dakota, where biologists found no strutting males for the first time in 2025.

Kirol is concerned about the future of northeast Wyoming’s sage grouse. He stated that the population has been steadily declining for the past two decades.

“The problem with northeast Wyoming is the birds are just constantly losing habitat, and they’re never gaining anything,” Kirol told me. “I’m hopeful that we’ll still have birds here in 50 years, but we’re going to get to a point where, if the numbers get too low, then any natural event might wipe them out.”