In September, Lander police arrested local resident Kayvon Powell for interfering with an officer during a traffic stop on his way home from work.

Powell quickly got into a shouting match with Sgt. Ron Wells after being pulled over for reckless driving.

Wells demanded a driver’s license, which Powell did not have, and requested that Powell roll down his car window, which he claimed was broken.

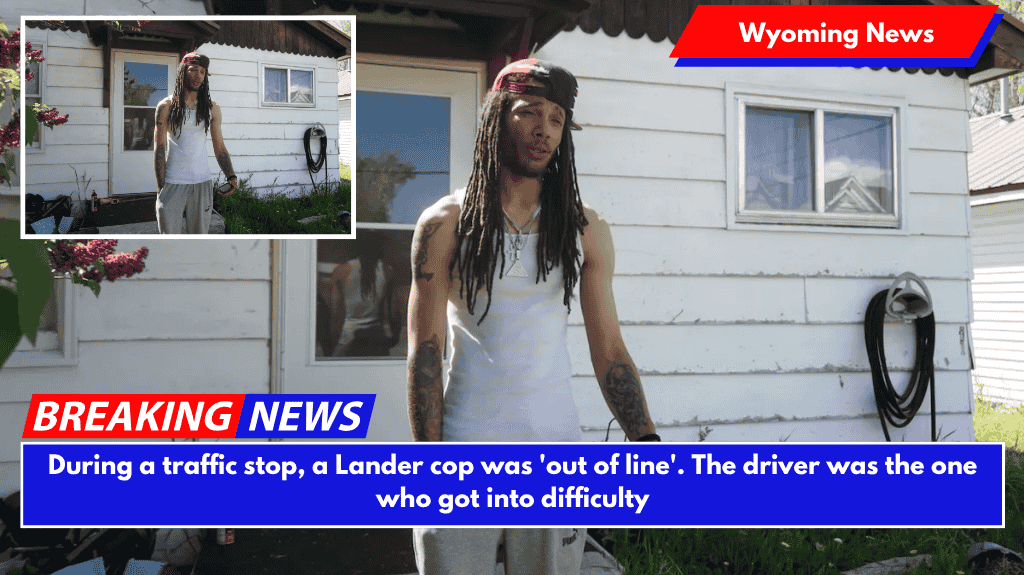

Powell, a 33-year-old Black man with dreadlocks, tattoos, and gold veneers, believed Wells was being aggressive after the officer opened his car door without permission.

Powell repeatedly requested that a supervising officer come and observe the interaction.

“The only thing I was concerned about was my safety,” Powell later admitted in court. “I want your superior here so I can make it home.”

By the end of the encounter, Wells and another officer had maced and jailed Powell, removing some of his long dreadlocks from his head during the rough arrest.

Powell took his interference charge to trial, but the jury found him guilty. The jury did not find that he resisted arrest, even as he was dragged from his car and roughly handcuffed to its trunk.

The Lander police chief and the judge who presided over Powell’s criminal trial both stated that Wells was overly aggressive.

“Sgt. Wells was out of line, absolutely 100% out of line,” Fremont County Circuit Court Judge Jefferson Coombs said during Powell’s April sentencing, describing the officer as going “off the rails.”

Wells also questioned his own actions following the incident, according to Chief Kelly Waugh, who was captain at the time. Wells told Waugh on the day of the arrest that he felt he had “lost his cool,” the now-chief told WyoFile via phone.

“[Wells] takes full ownership that he did not handle himself appropriately that day,” according to Waugh. The chief declined to comment on personnel issues or whether Wells was facing disciplinary action, but he was impressed by the sergeant’s willingness to accept responsibility for his actions and believed that self-accountability would be a powerful motivator for improvement.

Wells did not respond to WyoFile’s emails seeking comment.

Powell was placed on probation with a suspended 45-day jail sentence hanging over his head. He also still carries the raw emotions from the arrest and his subsequent treatment at the jail, where Fremont County sheriff deputies roughly forced his head down onto a counter after accusing him of looking at them in an unfavorable way, according to body camera footage.

Powell’s treatment in jail was not part of his criminal trial, but it could be relevant in a civil case if he files one.

The public defender’s office is appealing his conviction, according to court records.

Powell was convicted for his role in the encounter eight months after it occurred. Wells’ actions drew criticism from a judge and his boss, but it is unclear whether he faced any further consequences.

The episode calls into question accountability in Wyoming communities, both for police officers and residents charged with crimes.

Powell was not comforted by Wells’s expression of regret over how the arrest was handled.

“He never ‘took ownership of it’ in court or in his police report,” stated Powell, “where it really mattered, where my life was concerned.”

Accountability Questions

Powell ran into the police chief at a downtown gas station a few days after being sentenced in April. Powell approached Waugh and secretly recorded their conversation on his cellphone.

The chief, while acknowledging that Wells was acting within the scope of his duties, admitted to Powell that “what he [Wells] did was very unprofessional.”

Powell then informed the chief that he intended to sue the department, prompting Waugh to end the conversation. At that point, Waugh later told WyoFile, the case needed to be handled by lawyers.

If Powell takes legal action against the department, it will be a relatively rare case in Wyoming.

According to a report from the state insurance pool in charge of covering Wyoming law enforcement officers, only two constitutional claims were filed against Equality State officers last year, including the violation of civil rights Powell is alleging.

In 2023, there were eight such claims, and 2020 saw the most constitutional claims made against officers in recent years, with 13.

Academic researchers estimate that fewer than 1% of people who believe police officers have violated their rights ever file a lawsuit. People who sue the police face a high bar for legal victory, as federal court precedent gives officers broad discretion for actions taken while on duty.

According to the Harvard Law Review, cases that survive motions to dismiss are only successful about 15% of the time, and juries tend to award lower financial judgments than in other civil cases.

Powell’s story also raises the question of whether his appearance made his life in Lander more difficult.

Powell is a complicated figure; while he is determined to defend his rights on the street and in court, the judge claims he was dishonest on the witness stand after choosing to testify in his own trial.

Powell said he moved to Lander from Charlottesville, Virginia, following the Unite the Right rally there in 2017. He was horrified by the overt racism and violence that swept through the southern city, as well as the fact that local officials did nothing to stop it.

People told him. Lander was a quiet town, he stated.

“I guess if you can blend in a little better than me, it might be,” Powell told WyoFile in an interview from his home.

Waugh denied that Powell’s appearance influenced his treatment by police. As a law enforcement agency on the outskirts of the Wind River Indian Reservation, his department polices one of Wyoming’s most diverse communities, he said, and has worked hard to foster community relationships, including those with people of color.

“Racism is so far from the Lander Police Department’s actions,” he told me.

Powell admitted on the witness stand that he had been repeatedly cited for driving without a license. He believed the police were always out to stop him, but he told the jury that officers “weren’t smart enough” to catch him. He had previous interactions with Wells that left a bad impression, he said.

Similarly, Waugh stated that the department had run-ins with Powell prior to his arrest in September.

“Oh, you know it all, I remember,” Wells told Powell during their shouting match.

An arrest

Powell’s arrest on Sept. 3 stemmed from an incident that occurred months earlier, in July 2024. Powell was walking to a gas station when he was punched by Mario Cabanas, another Lander man with whom he had a dispute. Cabanas was convicted of assault, and the judge ordered him to pay thousands of dollars for Powell’s medical bills.

However, Cabanas, who the prosecution called as a late witness in Powell’s interference trial, stated that this did not appear to resolve the issue for Powell. Cabanas claimed Powell saw him driving on September 3 and pursued him.

Powell denied the allegation during his testimony, claiming he did not recognize Cabanas. Later in the day, the prosecution showed the court a cell phone video Cabanas took, which, according to his testimony, captured Powell closely following him.

Powell was cited for reckless driving, but the prosecution dropped that charge after he stated his intention to take it to trial, according to Powell’s testimony.

On September 3, Cabanas called the cops and told them Powell had seen him downtown and was tailgating him. Wells responded, and another officer followed suit, pulling Powell over.

WyoFile did not attend the trial, but obtained an audio recording from the Fremont County Circuit Court. WyoFile also examined Wells’ body camera footage, provided by Powell, as well as footage from his own cell phone. Audio from other parts of the footage was played for the jury.

In the audio, Wells raises his voice after approaching Powell’s car and asking him to roll down his window, which he does not. Powell later testified that the window had been broken.

Powell claimed he could afford to drive the beater car, a 1993 Crown Victoria, to and from the job he needed to support his two children.

Wells opens the door and angrily informs Powell that he was “trying to run people off the road.” Powell starts yelling back, asking what evidence he has.

Wells then tells him to open his door, which Powell declines to do. Wells opens the door and asks for his driver’s license and proof of insurance.

Powell continues to yell, demanding “a superior” and later “a white shirt”—the uniform he claims law enforcement supervisors wore in Charlottesville.

Wells eventually calls his then-captain, Waugh, who is off duty. “He wants my superior down here,” Wells said into his phone, sarcastically. He later laughs at the request.

On the call, Wells also asked Waugh if he could arrest Powell for interference because he refused to give the officer his driver’s license. “He is absolutely not complying,” Wells stated.

Powell, on the other hand, presented the second responding officer with a casino identification card from the Eastern Shoshone Gaming Agency. Powell stated in court that the officer approached him calmly and respectfully.

Waugh told WyoFile that a supervising officer is not required to report to a crime scene if a suspect requests one. In such a situation, a supervisor would typically respond to monitor the incident, according to Waugh, but Wells was the highest-ranking officer on duty that day.

Wells informed Powell that he was being arrested, and in the video, Powell can be heard saying he is getting out of the car before the two officers take him into custody. He is then placed against the car and handcuffed.

Dash camera footage from Wells’ car shows the officers shoving Powell into the trunk of the Crown Victoria twice before placing him in the back of the police vehicle.

The second officer pepper sprayed Powell while he was in the back of the police car, but no video of this was obtained by WyoFile.

According to Wells’ arrest affidavit, the other officer used the spray because Powell’s feet prevented the door from closing. Powell denied it. The audio from the ride to jail shows Powell in a lot of pain from the pepper spray in his eye.

Another section of body camera video from inside the jail shows deputies pushing Powell’s head into a counter and grabbing him by the neck after determining he was staring at Wells while handcuffed.

“You’re not going to eyefuck us in here,” one deputy told him, according to the video. “That’s not a crime,” Powell said.

According to Undersheriff Mike Hutchison of the Fremont County Sheriff’s Office, there have been no complaints about Powell’s treatment in jail. WyoFile gave Hutchison a copy of the body camera footage, which he reviewed.

Powell “disregarded reasonable requests” both during his arrest and inside the jail, Hutchison told WyoFile via email. “The deputies intervened when he exhibited a combative and aggressive demeanor while in custody. Although some coarse language was used, the Deputies’ reaction was within the scope of our policy.”

Powell does not believe he has ever physically resisted arrest. He stood up to an aggressive officer, he claimed, and was punished for it. “If someone telling you they don’t like what you’re doing is going to set you off to the point that you’re going to beat, mace and pull someone’s hair out, then that’s not the job for you,” he told me.

Waugh said Wells’ actions during the arrest were out of character for the veteran officer, who has been with Lander for 24 years. “We’re all human beings,” Waugh stated, and “some days get to us too.”

As a supervisor, Waugh stated, “I usually spend more time trying to get [officers] to understand what they did and take ownership of their actions.”

The sentence

Powell was sentenced two days after the jury convicted him. Judge Coombs heard testimony from the prosecutor, who called Powell a scofflaw.

Then he heard from the public defender, who stated that her client had learned his lesson and now had a license. Finally, Powell addressed the court, describing how he was beaten by police while trying to advocate for his safety.

The judge then said his piece. “There’s different theories out there as far as how judges should explain themselves,” he told me. “I’ve heard some judges say, ‘if I never say it, I can never get in trouble for it.'”

After describing the case as “unique,” Coombs paused for 20 seconds. “Well, I’ll just say it. I think Sgt. Wells was completely out of line. Was he acting outside the scope of his legal duties? The jury said he wasn’t, which is fine. I accept that.”

However, the judge ruled that the officer acted outside of department policy. “As soon as Mr. Powell didn’t open his door, Sgt. Wells sort of went off the rails,” Coombs recalled.

Powell, on the other hand, did not “one time” respond meaningfully to Wells’ questions, according to Coombs. He gave Powell a suspended jail sentence.

Finally, the jury found Powell guilty of interference, and “therefore, Sgt. Wells was in the lawful performance of his duties,” Coombs stated. “Even though he was certainly not the poster child for how a police officer should act during a traffic stop.”