Rock Springs City Councilman Rick Milonas didn’t mince words during a city council meeting this week when the discussion went to employing goats to eat away vegetation that is partly to blame for local flooding.

“Looks like a jungle down there,” Milonas remarked of the results of a prior $50,000 goat grazing project that finished this spring. “I think that made things worse. “Whenever you clip a branch or a plant, they go crazy.”

The council was debating a resolution authorizing a $58,000 contract with LS5 Livestock Co. to bring 150 goats to clear vegetation at the Killpecker and Bitter creek confluence. The measure passed 5-1, with only Milonas dissenting.

Mayor Max Mickelson defended the scheme, stating that the purpose is not aesthetics, but flood control.

“Large brush that gathers debris in a flooding situation has been removed,” Mickelson said reporters. “And what is left now is grass. And when there is a flood, grass lays down. Shrubs are powerful and cause clogs.

Milonas asked for details and success indicators, wondering aloud how the city could say the initiative was effective.

However, Milonas believes that this is about more than just goats.

“This whole thing is just so deep,” he said in a follow-up interview that included topics ranging from tainted water to alleged local government corruption. “This is simply another $108,000 thing they threw at it. “The whole goat thing is insane.”

Livestock Solutions

One of the goat wranglers working the creek beds in Rock Springs with 150 goats is Josh Skorcz. He’s seen firsthand how floods can rush down from Wyoming’s Red Desert into Rock Springs without warning.

Skorcz, a former environmental engineer at the Black Butte coal mine from 2012 to 2016, watched a flood that began far away from the mine site but finally rushed into Rock Springs.

“It did not even rain at the mine. Skorcz noted that it poured farther out in the Red Desert drainage basin south of the highway. “And it ended up flowing into our mine at the time and overflowing all the way to Rock Springs. I recall calling the city and telling them, ‘Hey, you’re going to have water heading your way.

Rock Springs is taking advantage of hungry goats’ capacity to devour plants and undergrowth that traditional grazing animals won’t touch, such as greasewood and perennial peppergrass, a noxious weed.

The goat operation, which was approved by the municipal council on Tuesday, will last six to eight weeks. The animals will be contained by electric fence and hard panel enclosures. But there’s a water quality twist: Skorcz intends to truck in water rather than allowing the goats to drink from the creek.

“The water quality on that Killpecker Creek is really bad,” Skorcz told me. “So we’re not going to water the goats in there.”

Skorcz’s decision reflects known water quality issues in the area. A 2018 watershed assessment discovered contamination in Bitter Creek and Killpecker Creek.

“A TMDL (Total Maximum Daily Load) investigation has recently been completed on Bitter Creek and Killpecker Creek targeting fecal coliform and chloride,” according to the research findings. “A water quality management plan is currently being initiated.”

The city’s contract with LS5 Livestock Company addressed the issue, stating that “supplemental watering will have to take place for the goats.”

Flood History

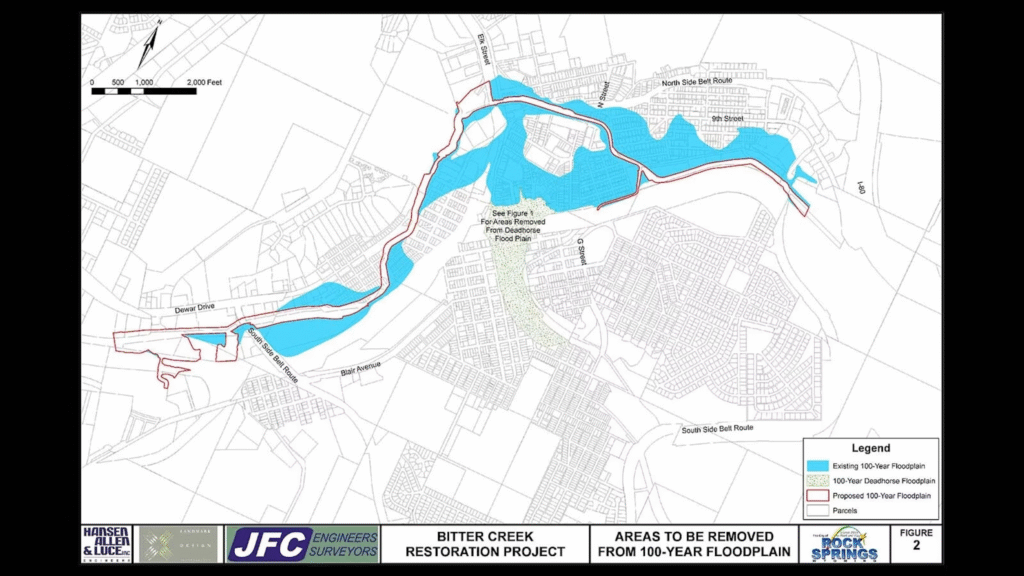

In a phone call with Cowboy State Daily, Mickelson elaborated on the city’s flood mitigation strategy. He highlighted how Rock Springs has experienced recurrent flooding since the Union Pacific Coal Company altered the creek bed decades ago, causing long-term concerns for people along the eastern corridor.

The city’s website relates the story: “In 1916, the Dead Horse Canyon Creek drainage ditch was constructed in partnership with the Union Pacific Railroad to control storm water into Bitter Creek, but in 1924 a devastating flood still affected the railroad, coal mines, and residents living along the creek banks.”

The railroad constructed a diversion channel to divert flood waters away from the train tracks and coal mines, but the flood hazard persists, particularly when the channel is filled with dense vegetation.

“We see the kind of flooding where the creek backs up, and then people’s basements get flooded,” Mickelson talked about. “So all of the folks that live in that area are compelled to maintain flood insurance.”

The mayor noted that goats can reach regions that big equipment cannot, making them critical for clearing vegetation that causes debris dams during high-water periods.

“This particular area that this section would address is one that is bordered by private property and is not accessible to crews with equipment,” he explained, glad that the council opted to send in the goats once more.

Past Corruption?

For Milonas, sounding an alarm about the city’s two goat contracts connects to deeper concerns about city governance and financial accountability.

He cited the conviction of former Mayor Tim Kaumo, who was fined more than $5,000 for official misconduct in using his position to gain engineering contracts for his own business.

“The former mayor has been indicted. He has been found guilty. “I mean, that’s on the record,” Milonas added, lamenting the cost of the goats.

“We can put a new roof on our civic center for $100,000,” Milonas added, vowing to keep highlighting other things he believes the city needs besides brush-chewing goats.

“Those poor people at animal control, they need a new facility so bad,” stated the rookie council member. “I can’t believe the mayor’s not even talking about trying to find money for this animal control facility.”

Goat Attack

While tensions swirl in city hall, Skorcz will be down in the creek bed with his goats, tending to the electric fence and making sure no neighborhood dogs try to tangle with the herd.

The goats, a combination of Boer and Spanish types, will work for 10-14 hours every day.

Among them is Vincent Van Goat.

“The folks we got him from, that’s what they named him,” Skorcz recalled. “Vincent, he’s more of a pet than anything, but he’s going to be in there.”

Skorcz retains unshakeable faith in his goats, despite criticism from others and a desire to avoid local political squabbles.

“I think using something the most natural way that you possibly can to do something is better than chemicals,” according to him. “And I think that in this situation that this is a good solution to the problem.”