The other day, economist Tyler Cowen made an offhand observation that surprised me a little: the French now have “the longest financed retirements ever seen in the history of the world.”

Verifying the “history of the world” part is beyond my historical expertise. However, the OECD’s 2023 Pensions at a Glance report confirms that French retirees are enjoying many years off the job.

According to the report, the average age of French men who left the labor force was 60.7. At that point, they have an 84-year life expectancy, which means they can expect to retire for 23.3 years, which is longer than any of the other countries examined by the OECD.

French women can expect to retire at the age of 26.1, which is less than Luxembourg, Spain, Slovenia, and the world leader, Saudi Arabia, but still very high. (The Saudi case is more about women working fewer and shorter hours than in more liberal countries, rather than retirement policy.)

French men and women can expect to retire for more than five years longer than Americans.

In fact, the French government fell this week in part because opposition parties demanded that the centrist coalition in power reverse its decision to raise the formal retirement age from 62 to 64.

Funding 23 to 26 years of retirement per person is costly, which is why President Emmanuel Macron raised the age in the first place, but with the elderly voter bloc only growing in size, failing to pay that money out could be politically suicide.

Retirement, American-style

As a non-Frenchman, this fight naturally makes me think about the upcoming retirement battle in the United States. Our Social Security trust fund is expected to be depleted in eight years.

Under current law, retirees will face an overall benefit cut of about 23%. Everything I know about how the US government operates tells me that it will not reach that point. The question then becomes, what would a deal to prevent those cuts look like.

One obvious way to avoid the French predicament is to raise the retirement age, as Macron did. The aging problem that is affecting the pension systems of the United States and other wealthy nations has two components.

One is that, due to the size of the baby boom generation, more people are reaching retirement age than ever before. In 2022, the number of retired workers receiving Social Security for the first time reached 3.4 million, up from less than two million in 2000.

Raising the retirement age does not resolve this issue. However, it addresses the second issue, which is that the average length of retirement has increased as nutrition and medicine have improved. A man born in 1900 and turning 65 in 1965 can expect to live another 12.9 years.

According to the Social Security Administration, a man born in 1960 who turns 65 this year can expect to live for an additional 18.4 years. Even accounting for the trend of people claiming Social Security later in life, that’s a significant number of extra years that the program must pay out per male retiree.

Between 2000 and 2022, the United States gradually increased the retirement age for full Social Security benefits from 65 to 67. However, the majority of bipartisan proposals to reform Social Security (proposals that have a chance of passing) call for an increase in the retirement age.

Two years ago, Senators Angus King (I-ME) and Bill Cassidy (R-LA) proposed raising the normal retirement age to 70. The Bipartisan Policy Center gathered some former politicians and experts from both parties to develop a plan that ultimately advocated for a 69-year-old retirement age.

One of the primary political benefits of raising the retirement age is that it is a benefit cut that is not as obvious as other benefit cuts.

However, it does represent a cut, and potentially a significant one. A 67-year-old woman can expect to live another 18.5 years. Assume she must wait until she is 70 years old to claim the same benefits she can now at the age of 67.

That eats up three of her 18.5 years of expected benefits, representing a more than 16 percent cut. With shorter lifespans, the cut for men is even larger in percentage terms.

The most important question, however, is whether it is an overall benefit cut or a regressive one. There is strong evidence that it is the latter.

Death inequality and Social Security

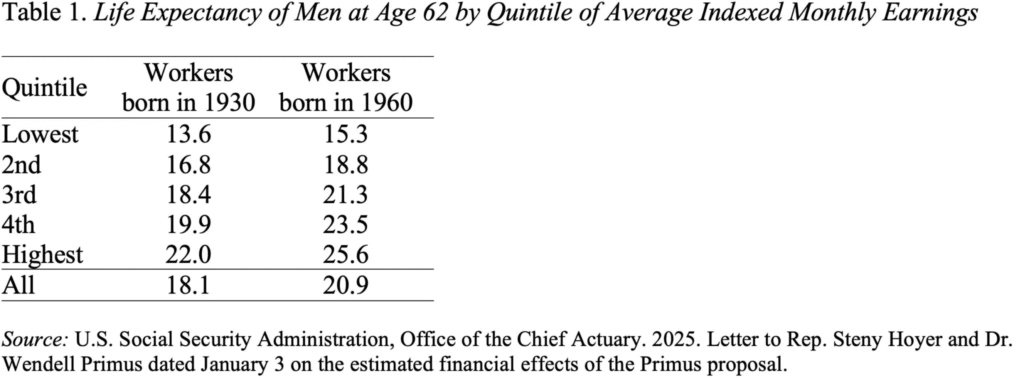

The eminent Social Security expert and economist Alice Munnell recently highlighted a chart from the program’s actuary’s office that underlined a very concerning gap and trend:

If you don’t speak Social Security jargon, this can be difficult to understand. It essentially compares two groups: men born in 1930 considering retirement in 1992 and men born in 1960 considering retirement in 2022. In both groups, there is a significant difference in life expectancy between those who earned the least and those who earned the most.

In 1992, high-income men could expect to live 8.4 years longer than low-income men. They may be able to add 10.3 years by 2022. (“Highest-earning” refers to the highest-earning fifth. This is not Elon Musk money: in 2020, being in the top quintile as a man meant an average monthly income of at least $6,391, or $76,692 per year.

To put it another way, not only is there a significant difference in life expectancy between rich and poor people, but the gap appears to be increasing.

This casts retirement age discussions in a different light. Assume we want to raise the early retirement age (now 62), rather than the normal retirement age (now 67), at which retirees can claim reduced benefits. If we raise the age by three years, men in the highest income bracket will receive a cut of three divided by 25.6, or approximately 11 percent.

Men in the lowest income bracket receive a cut of three divided by 15.3, or nearly 20%. The specific numbers vary depending on whether you’re considering raising the normal retirement age or looking at female workers, but the overall message is the same: raising the retirement age results in a larger cut for poorer workers.

Recently, economists Henry Aaron of Brookings and Mark Warshawsky got into a heated debate about how to interpret these numbers. Warshawsky argues against using life expectancy numbers like those above because they inevitably require projections (we don’t know, of course, how long people who retire in 2022 will live, owing to the fact that the majority of them haven’t died yet), and for limiting analysis to men aged 65-69.

Aaron claims that this is too restrictive (everyone, including insurers, relies heavily on life expectancy projections) and ignores the fact that women’s lifespan inequality has increased.

To my untrained eye, Aaron has the upper hand in this particular dispute. However, it is important to note that raising the retirement age does not have to increase the lifespan gap between rich and poor. If rich men continue to live 10 years longer in retirement than poor men in 30 years, an increase in the retirement age will still disproportionately affect poor men, even if the gap has not grown.

Splitting the difference

The traditional Republican approach to Social Security has been to call for benefit cuts to cover the entire shortfall, while the traditional Democratic approach has been to rely solely on tax increases. None of these have a chance in hell of happening, especially if the Senate filibuster remains in place.

I doubt there are 50 Republicans in the Senate who are willing to vote for major benefit cuts right now, let alone the 60 required. Similarly, I believe the chances of Democrats ever electing 60 senators willing to pass a massive payroll tax increase, even on the highest earners, are nearly zero.

If there is to be reform before the trust fund runs out in 2033, it will have to be bipartisan and require significant concessions from both sides. And I believe a retirement age increase will be part of the deal.

If that happens, the best option available is the one proposed by Wendell Primus, Tara Watson, and Jack Smalligan in their recent Brookings reform plan. They would raise the retirement age—but only for the top 40% of earners.

The majority of retirees would see no increase in age, whereas the top fifth of earners would see it rise to 70. Those in the 60th to 80th percentiles would experience smaller increases. Along with other progressive benefit cuts and tax increases, the plan would address the program’s solvency issue.

This retirement age change would complicate the system by requiring people to look up their specific retirement age based on their income. However, it is the only plan I’ve seen that prevents the most common type of benefit cut from being painfully regressive.