The University of Wyoming football team hosted the Arizona Wildcats in the first game of the 1969 season. It was college football’s centennial year, and 20,000 people packed Memorial Stadium in Laramie on September 20 of that year.

In the second quarter, split end Ron Hill, a transfer from Northeast Junior College in Sterling, Colo., caught a pass from quarterback Ed Synakowski for the Cowboys’ first touchdown of the season.

Less than a month later, Hill and the other 13 Black varsity players were kicked off the team when they arrived at Coach Lloyd Eaton’s office on Friday morning before the Brigham Young University game.

The Mormon Church, which owns BYU, did not allow African Americans to become priests, and the Black 14, as they became known, sought to protest the policy by wearing black armbands. But as soon as Eaton noticed the players’ armbands, he led them to the fieldhouse bleachers and told them, “You’re no longer Wyoming Cowboys.”

Hill, 77, died last month in his home state of Alabama from cancer, leaving only ten of the Black 14 survivors.

Hill grew up in Bessemer, Alabama, with eight siblings and a father who worked in a steel mill.

When Hill was about 15, he moved to Denver with his oldest brother, Roosevelt Hill. He excelled as an athlete at Manual High School and was teammates with Don Meadows, another future member of the Black 14.

After playing at Sterling, he transferred to the University of Washington in the fall of 1968, but redshirted that season. In May 1969, Powell Tribune editor Dave Bonner went to Sheridan to cover a Cowboys intra-squad game, and three Black players caught his attention.

“Among the other standouts were split end Ron Hill, tailback Rick Marshall and defensive back Ivie Moore,” according to Bonner. “Hill caught four passes for 174 yards and showed great speed in taking two of the tosses for TDs.”

Moore was also a member of the Black 14 with Hill.

Hill completed the semester and then left the University of Wyoming after trustees and Governor Stan Hathaway supported the coach’s decision to remove the players for the season.

Nine months after being fired from the team, he received a devastating blow to his young life when his brother, the director of the Black Studies program at Colorado University-Denver, was shot and killed.

Roosevelt Hill had taken a couple of his students and his wife to the Colorado State Penitentiary to speak with the Black prisoners there about “Awareness of the Black Man.” On the way back, they stopped at a gas station in Colorado Springs to fill up the Colorado University vehicle they were driving.

He handed the attendant a CU credit card, a soldier stationed at nearby Fort Carson who had recently returned from a tour in Vietnam and was working part-time at the gas station.

The attendant apparently suspected that the car and credit card had been stolen and went inside to make a few calls. When the attendant failed to return for an extended period of time, Roosevelt, his wife, and one of the students, all unarmed, entered to investigate. The attendant was in a small office, and accounts of what happened varied, but tempers flared.

The attendant took a.38-caliber revolver from the drawer and shot Hill dead. The county prosecutor convened a grand jury within a few days, and after hearing testimony from witnesses, including Roosevelt’s wife, the jury declined to charge the attendant, apparently accepting his claim of self-defense.

Two Black state senators and civil rights organizations protested, demanding an investigation by the Colorado Bureau of Investigation. They also demanded that the prosecutor file charges directly, but this did not occur. The soldier was quickly moved to another Army base.

Six months later, the Hill brothers’ mother died, dealing Ron another blow. But he persisted. He worked for the Burlington Northern Railroad for 13 years, earned a degree in education, and taught and coached physical education at two middle schools in Denver, according to his friend and Black 14 roommate John Griffin, a 1969 junior college transfer to UW who was the Cowboys’ leading receiver when he was kicked off the undefeated and 12th-ranked team.

Hill was a father to a son and daughter.

Ron Hill attended a “reunion” of the Black 14 players and some of the 1969 administrators in September 1993, which was organized by the head of UW’s newly established Black Studies program.

In a 2010 interview, Hill stated that he and Moore worked in Denver after leaving the University of Washington. He was the best man at Moore’s wedding. “Me and Ivie assumed [the dismissal from the team] was something that happened at a certain time and place, and we moved on.

We left knowing we had won. It was all a lesson. It made me more mature, but the struggle continues, not just in Laramie but across the country.”

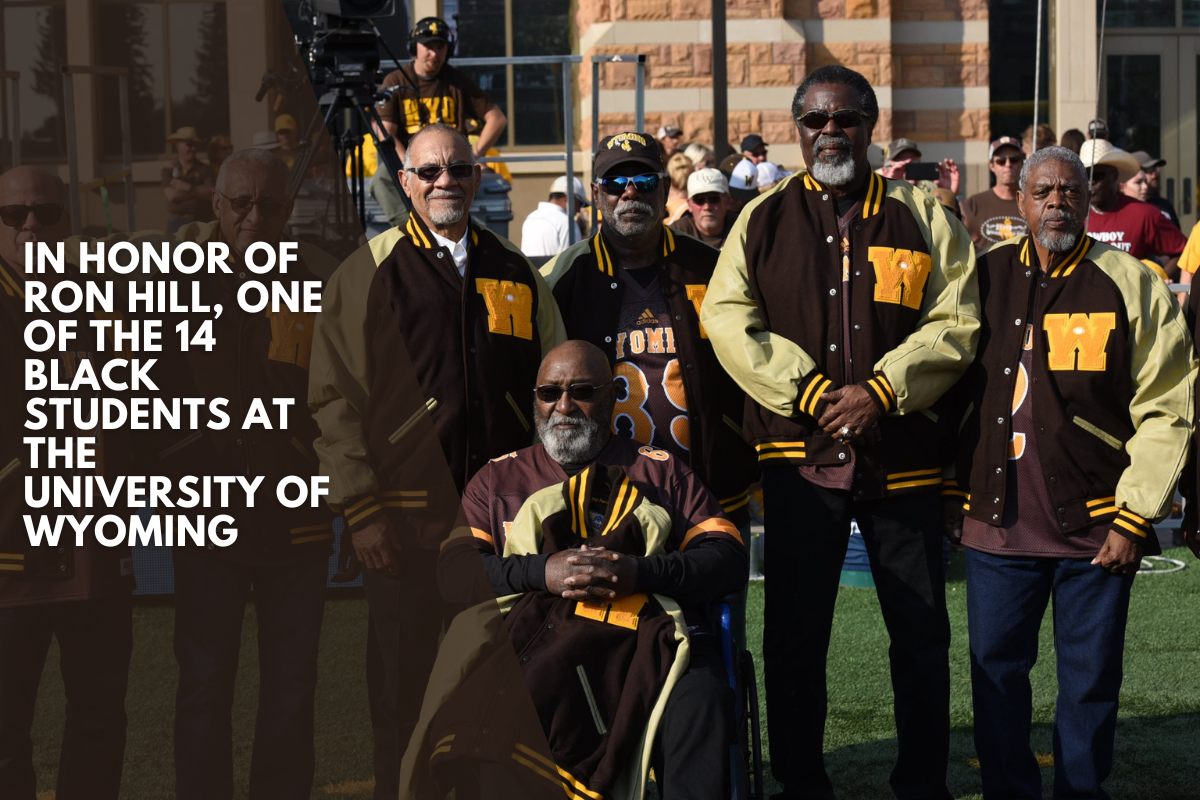

Hill continued to participate with the Black 14, attending the 50th anniversary commemoration in September 2019, when UW’s president and athletic director apologized to the expelled players.

At the event, Hill renewed his friendship with Ohio’s Black 14 teammate Lionel Grimes. In a recent email, Grimes stated: “Ron and I grew very close by talking non-stop on the phone after meeting in Laramie in 2019, and he was so thrilled when he and I started FaceTiming.”

Hill previously worked at a plant that converted plastics into fiber. Moore moved from Arkansas to live and work with Hill for a while.

Hill died on July 5, in Florence, Alabama. The family will hold a private memorial service for Hill, according to his page on the Thompson & Son Funeral Home website.

The first of the Black 14 to die was James Isaac of Hanna, Wyoming, the son of a Union Pacific railroad worker. He died in California in 1976. Don Meadows, who returned to the team in 1970 and was named to the All-Conference First Team, died in 2009. Earl Lee, a highly respected teacher, coach, and principal in Maryland, died in 2013.