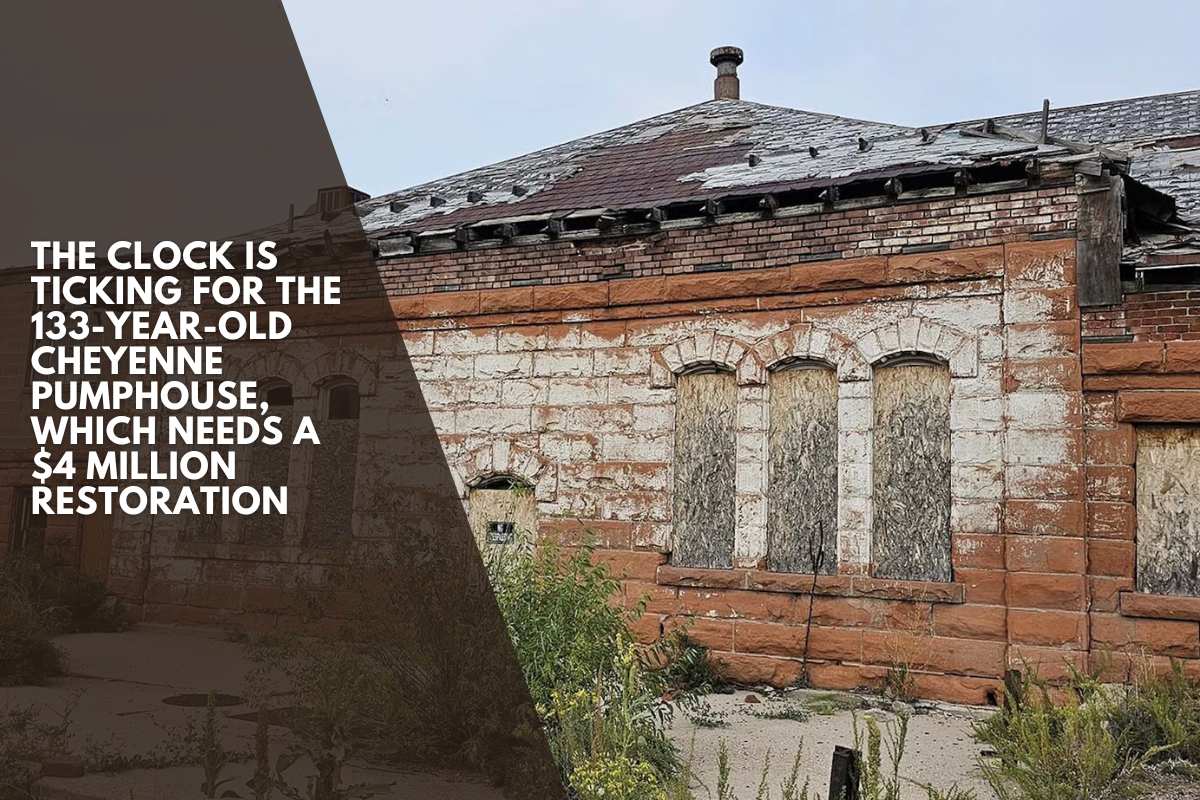

CHEYENNE — It’s disheveled but proud, with clean lines made of red Ashlar-cut sandstone blocks hauled in from the Horsetooth Reservoir, according to historical records.

It’s the same red sandstone used to construct the historic Cheyenne Depot. And it is the same Richardsonian Romanesque architecture, with a grand, monumental appearance reminiscent of Roman antiquity.

That architecture has helped to establish the former Union Pacific Depot as a focal point in Cheyenne’s downtown. Unlike the Depot, which was restored in the early 2000s, Cheyenne’s Historic Pumphouse has yet to find its champion.

It needs someone willing to spend the $4 million required to restore the building to its former glory.

Weeds have sprouted up all around the pumphouse like a crazy, cast-off wig, hair all akimbo and pointing to the sky. Hair made of wispy grass sprigs mixed with spiky, tall plants that resemble mullein in bloom on an alien world.

This wild wig is adorned with glorious sunflowers, their heads bowing to the sun, as well as a dark purple shrub around the corner that resembles a miniature forest of ruby lettuce.

The wildness of the space makes it impossible not to feel like a trespasser, even when standing there with Cheyenne City Project Manager Paul Belotti.

“This is actually the back of the pumphouse,” he explained, gesturing toward the scene. “And where we are standing used to be a reservoir that went all the way out to Lincoln.”

Every day, water flowed into that shallow reservoir from Crow Creek and was distributed to Cheyenne residents in need as they turned on their taps.

Bells would ring at specific times of the day, including 5 p.m., to notify residents of increased water pressure. The 5 p.m. bell signaled the watering of all the fancy, green lawns in what would become Wyoming’s state capital.

From What A Cosmopolitan City Needs …

The Historic Pumphouse was constructed in 1892 for a city that was expanding so rapidly and successfully that it had earned the nickname Magic City of the Plains.

Having a municipal water system of this caliber puts Cheyenne on par with some of America’s largest and best cities, according to Historic Cheyenne Inc. Vice President Maren Kallas, who has been researching the facility’s history.

“They were very proud of it when it opened,” she told me. “They described it as a veritable young depot. “Having a municipal water system like that made you a true cosmopolitan city.”

Kallas added that at the time, many people had never seen a bathtub.

Wyoming had only been a state for two years in 1892, and many still considered it part of the frontier. In contrast, Cheyenne appeared out of nowhere, like an overnight pop-up city.

“This was like a really new, modern thing to have city water,” Kallas recalled. “What made Cheyenne unique was our cosmopolitan nature. We had opera houses, a variety of languages were spoken here, and people traveled from all over the world by rail.”

The pumphouse was not Cheyenne’s first. It was actually the second. The city had outgrown its previous one in just over a decade.

“The population just kept growing and growing,” Kallas said. “They built the first pumphouse over where the State Library is at 28th and Central.”

It didn’t produce enough water pressure to extinguish fires, and the untreated water tasted and smelled bad. It would not help Cheyenne build the reputation she desired.

“So, they built the new pumphouse along the banks of Crow Creek, in the same architectural style as the depot,” Kallas told me. “They took a lot of pride in it, and they made great improvements to it.”

… To A Society Nuisance.

The new pumphouse included filter beds to clean the water, and the water pressure was significantly increased. Newspaper articles waxed poetic about how she was laying the groundwork for Cheyenne’s bright future, using such vivid and affectionate language that it’s difficult to imagine how she ended up in such a neglected state today.

Homeless people now sneak into her once-proud shelter at night, seeking refuge from Wyoming’s winds and storms.

“I come in here with one of the compliance guys, and we clean it out about once a month,” Belotti said, pointing to the debris, worn-out tennis balls, and baseballs that had mysteriously appeared. “All this happened in the last three weeks or so.”

Belotti returns every few days between cleanings to discourage people from bringing things in. That is all it takes to prevent them from reoccupying the space.

Belotti added that the problem worsens during the winter. People even build fires to stay warm.

That has made her a nuisance in civilized society. One issue that the city has decided to address.

A hollow space

Inside, the pumphouse is dark and hollow. Echoes are quickly absorbed into her silence, leaving only the graffiti on the walls to communicate.

Most of the script is not very legible. They are incomplete messages written in fancy letters with words that don’t make sense.

The most obvious of these messages is written in white ghost lettering, either painted or chalked on a rusted metal door in front of the building.

“Got a lot of time to waste when you’re getting wasted,” according to it.

It’s signed by “Heddy,” with the tagline “wrong-way kidz.”

If this were a scene from a Gothic novel, the message would be cryptic, warning of soul-sucking danger ahead. But it’s a sunny September day in Cheyenne. We can ignore such messages and pass through the dark portal safely, paying it no mind.

“There was a man who lived here with his family and ran this facility,” Belotti explained, gesturing to the dusty interior with its ragged and peeling paint. “They had living quarters in here for them.”

It’s difficult to imagine this space being filled with children’s laughter and other family-related sounds.

There would also have been the sounds of a massive Holly Duplex Steam Pump working around the clock to send water across Cheyenne, as well as coal being shoveled into it.

Andy Artist, the first pumphouse engineer, remains silent on the matter, assuming he is haunting this place at all.

Escape Artist

There are numerous funny stories about Artist. Like newspaper articles about how he saved a cow from an oncoming train by catching the engineer’s attention in the nick of time.

One of the more dramatic stories revolves around a disastrous sleepover.

The artist and his daughter were in the living room with three of her friends, who had come over for a sleepover. It was 9 p.m., and the girls were undoubtedly giggling despite the late hour, while dad was probably grumbling about young girls needing to sleep.

A rushing roar of distant water drowned out their conversation and engulfed them in seconds.

The artist and his daughter climbed up the dining room chairs to escape the flood, which was caused by a sudden storm that swelled the Crow Creek banks, bringing rushing water into their path. Her friends narrowly escaped by ripping the screen door at the top and slipping out onto the roof. The force of rushing water had pressed the door shut tightly.

The floodwater reached up to Artist and his daughter’s necks before receding, making it a terrifyingly close call for the family.

Other Cheyenne families were not as fortunate, according to Kallas, and newspaper articles about the flood continued for decades. People discussed how it altered their lives and disrupted their families.

The artist worked as a pumphouse engineer for just over a decade in total. Nonetheless, he died tragically young. His luck ran out in 1905, when he was discovered beaten and bloodied after a bar fight. He died three days later.

The pumphouse remained the pride of Cheyenne for another five years. By then, the city had outgrown her.

A new and larger facility was built near Roundtop, a newfangled, gravity-fed water system with roughly double the capacity of the pumphouse.

The pumphouse became an auxiliary facility, supplying water during times of high demand, such as fires and Cheyenne Frontier Days.

It was also useful for reducing dust on dirt and gravel roads.

Rare Piece Of Cheyenne’s Origin Story

In the 1920s, the facility was completely decommissioned, useful as a pumphouse no more.

The Cheyenne Street Department acquired the facility sometime in the 1930s, and later added a metal shed, probably in the 1970s according to Kallas’ research so far. It served as both maintenance garage and storage shed.

The metal additions prevented the facility from being listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Under the city of Cheyenne’s $4 million restoration plan, those newer, metal parts, would have to be removed, according to Belotti.

Cheyenne listed the pumphouse as a top priority in 2024, but the tide turned in 2025, with some councilors questioning the wisdom of spending so much to restore such an old building.

It was ultimately decided to put the facility up for sale — albeit with some restrictions — to see if a buyer could be found to take it on as a project instead, Belotti said.

Milward Simpson, who is chair of the Cheyenne’s Historic Preservation Board, said he is happy with the restrictions.

“It’s things like the purchaser is prohibited from demolishing the structure,” he said. “They’re prohibited from modifying or altering the exterior of the structure in any way that would make it ineligible for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places. And then they also ensure the exterior renovation or restoration complies with the Secretary of the Interior’s historic property standards.”

That will ensure that any future buyer has a genuine interest in historic preservation, or adaptive reuse, Simpson added.

Simpson believes the property is absolutely worth saving.

“It’s a crucial part of what we like to call in the historic preservation world, adaptive reuse, where you adapt an old building and re-use it for new purposes to help the economy — like meeting spaces, restaurants, retail outlets, that kind of thing,” he said. “The pumphouse can be a really important part of that.”

It’s also a rare piece of Cheyenne’s pioneer origins story, one that engineer reports have said is still solid and can be saved. There aren’t too many pieces of Cheyenne’s origins left, Kallas said.

“We wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for the Crow Creek,” she said. “Cheyenne sprouted out of this water. The tent city sprang up on the banks of the Crow Creek.”

Time Running Out

If no buyer is found by January, then the pumphouse is likely to meet a wrecking ball, despite engineer analysis that find the 133-year-old building is still structurally sound.

Belotti said that so far, there have been inquiries about the facility.

“I’ve had about six calls so far,” he told me. “More than I expected to see.”

The sales process is awaiting an appraisal, after which bids will be accepted for the building. Belotti anticipates the appraisal within a few weeks.

The building is amazing. Belotti explained.

“This is a pumphouse, an industrial building,” he explained, gesturing to the intricately carved stone. “Today we’d use tilt-up or precast concrete.”

The stonework, too, reflects the craftsmanship of the time. It has lasted longer than some more modern brick structures.

Simpson stated that not saving it would be sad.

“Cheyenne still smarts from some old wounds at having unfortunately chosen to tear down similar structures,” according to him. “The one that everyone points to, and current city council members will point to, is the old Carnegie Library building, which was a beautiful historic structure that was sadly demolished years ago. People like our historic preservation board do not want to see that trend continue.”

Simpson believes it’s a solid piece with the potential to become something grand again. Then it could carry forward a unique thread in the city’s pioneer history.

“These old buildings are really important to who we are and who we’ve decided we want to be economically,” he told me. “So, our stance is to keep the pumphouse. Let us restore it. Let’s invest in it and use it because it has the potential to generate a lot more money for us in the future than it will cost to tear down.”

Only time will tell whether this once-proud Cheyenne landmark can be restored.

Time is quickly running out.