The Wind River Food Sovereignty Project purchased this 30-acre farm in Fort Washakie, which was mostly used for hay production. The yards contained machinery and tools. Fences were showing signs of deterioration.

Two years later, a shift is underway. Old machinery has been removed, and a walled vegetable garden is overflowing with squash and melons.

A big high tunnel has been built, with immaculate rows of raised beds ready to receive soil and seedlings. Native flora, such as chokecherry bushes, have been placed along the creek; some may even survive the deer attack.

Near the farm entrance, circular paths wind around a garden with benches, flowers, and a shaded space for tribal elders to rest and ponder.

“This garden is a sanctuary,” Wind River Food Sovereignty Project Co-director Kelly Pingree told a throng at the grand opening celebration on Saturday. “A place for healing, peace and connection with nature.”

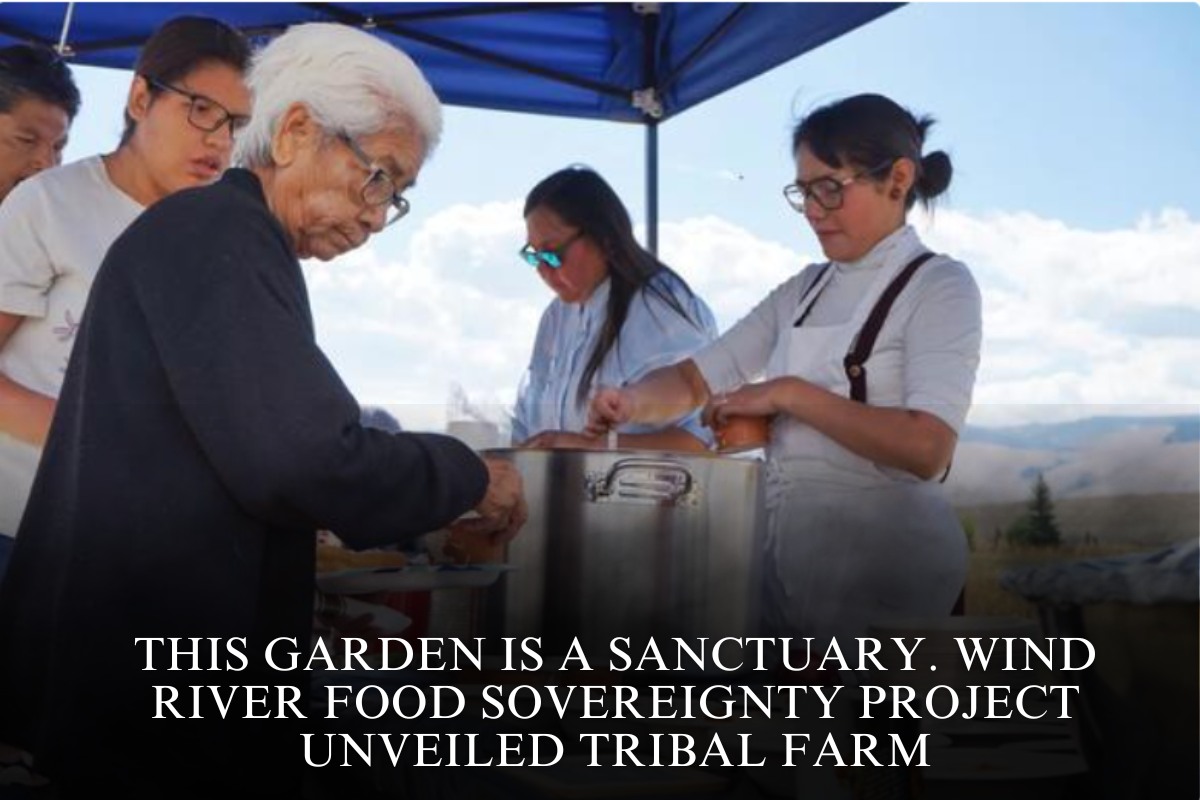

After the ribbon was cut, tribal members and others from the village filed through an elegant gate and into the newly constructed elder garden, forming a circle around drummers. After a song and prayer, it was time to dine.

Given the nonprofit’s mission to restore food production and traditions in Wind River Reservation villages, marking the event with bowls of buffalo stew and fry bread coated in chokecherry gravy seemed appropriate.

“As Native people, we always give thanks to Mother Earth for what she provides us,” Pingree told the audience. “And when we connect with our food, it reconnects us to the land, our ancestral knowledge, our spirituality, our prayer.”

Trout Creek Farm’s accomplishment represents the first steps toward a multi-year program to boost local production, access to healthy foods, tribal education, and other initiatives. However, it also represents the results of a $36 million federal revitalization award that numerous aspects of the reservation look to profit from.

The Food Sovereignty project hopes to share with everyone, said Pingree, clad in a vibrant ribbon skirt and standing beneath the flags of the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribes.

“I invite each of you to embrace this garden as your own,” she said.

A dream takes root

Hank Herrera created the Wind River Food Sovereignty Project in 2018. It was involved in reserve farmers’ markets and attempts to help indigenous food producers. Herrera died in 2020 from COVID-19 issues, but colleagues continued his work.

Herrera’s long-term goal has been to maintain a farm that can serve as both a living classroom and a vehicle for engaging tribal people in the production of traditional foods and plants. The goal was to find a neutral location that both tribes could use. “We wanted to serve everybody here,” Pingree told WyoFile in a July interview.

The land search took years. The organization, however, closed the Trout Creek Farm in late 2023. The original owner, who was aging, wanted the property to be sold to someone who would look after it properly. The non-profit organization promised to accomplish just that.

Private donations and grants enabled the Sovereignty Project to purchase the land. In July 2024, it also received a significant boost as one of the recipients of the federal “Recompete” experimental award program.

Wind River Development Fund, which applied on behalf of the Sovereignty Project and several others on the reservation, was one of just six grantees nationwide. The fund received $36 million, including $4.2 million intended for the Sovereignty Project’s ambitious objectives.

“We knew it would be a huge leap for us, because it’s basically quadrupling our staff over the next five years,” Wind River Food Sovereignty Project Co-director Livy Lewis said. “But we felt like we could rise to the occasion.”

The project began by hiring a farm manager and purchasing equipment. Clearing and preparing the land took months. This summer, staff planted seeds in a grow dome, tilled rows for a garden and began a pumpkin patch. They also began expanding work with education initiatives. More recently, they poured concrete and installed pathways to finish the elder garden.

Saturday’s opening certainly drew elders — but they were joined by families with babies, young adults and residents from nearby towns. Along with feasting, participants drank sweet plum-colored chokecherry tea, perused a table arrayed with traditional native foods like cattails and amaranth, and took in the views of the hulking Wind River mountains to the west.

First sprouts

It’s taken years of work to get to the point of harvesting garden crops and opening the elder garden. But for the Sovereignty Project, it’s still just the beginning of a story that will in some ways write itself.

“It’s the first of its kind,” Pingree said of Trout Creek Farm. “But it’s also to be self determined, to choose our own food ways. You know, that’s what food sovereignty is all about, is to define how we grow our own food, what we choose to eat, and how we distribute that.”

Ultimately, she stated, the nonprofit hopes to use its grant funds to create a healthier community. That entails increasing production enough to get their vegetables and fruits into schools, restaurants, and retirement homes.

Offering dirt plots for tribal members to grow their own food, as well as opportunities for children to learn the fundamentals of agriculture and nutrition. Facilitating the expansion of food banks and hosting cooking and preservation workshops.

Increasing resources to help reverse the habits that have contributed to high rates of diabetes and obesity among Indigenous peoples.

“But also teaching them their ancestral ways of being reconnected to the land, which has been severed for many, many years,” Pingree pointed out. “And so, to restore that and teach them to be proud of being able to stand up and say, ‘I don’t want to eat that anymore. “This is what I want to eat.”