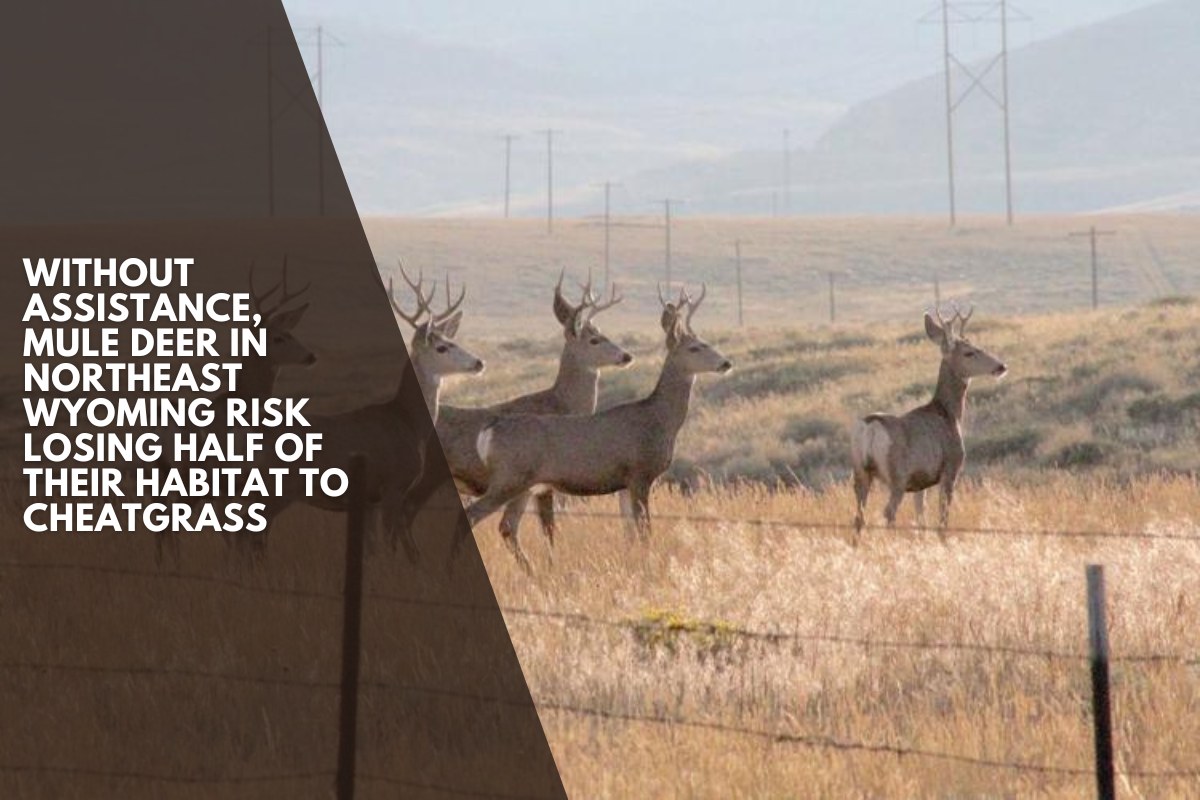

When thin shoots of cheatgrass are the first plants to green up in the spring, mule deer may nibble the tops in the same way that we might idly crunch last week’s pretzels on our office desks.

However, by early summer, the cheatgrass has turned brown and leggy. Mule deer are as eager to eat it as we are to consume the cardboard box containing those stale pretzels. They simply won’t do it.

Mule deer dislike cheatgrass so much that they will avoid an area entirely once it contains about 20% of the annual invasive grass, according to a study published in the journal Rangeland Ecology and Management in early September.

The authors of the study, all from the University of Wyoming, compared the movement patterns of 115 GPS-collared mule deer to range maps that showed plant cover variations. They discovered that even when cheatgrass covers less than 10% of an area, deer continue to browse. When it reaches 10-16%, they will start to avoid that area. Anything above 20% is completely unappealing.

Even more concerning, the study indicates that if cheatgrass continues to spread in northeast Wyoming over the next few decades, up to 50% of current good habitat may be rendered useless to mule deer.

The spread of cheatgrass is unlikely to be the final nail in the mule deer’s coffin, but it will be one of many factors contributing to their continued decline. Unlike many studies that focus solely on declines, this one contains a significant kernel of hope.

When cheatgrass is treated with herbicides in a targeted and strategic manner, land managers can begin to win the battle, and mule deer will return.

A perpetual plague

Cheatgrass has been a scourge of western landscapes for more than a century, having arrived from Europe and Asia nestled in seed bags and straw bales. Like most nonnative, invasive grasses, it did not evolve in this environment and quickly found a way to outcompete its native neighbors.

It “cheats,” germinating over winter to be the first grass to grow in the spring, depleting water and resources before native grasses, plants, and shrubs awaken from their winter slumber to seek nourishment again.

However, by early summer, cheatgrass has cured and lost any remaining nutritional value. It becomes a fire hazard, which is part of its evolutionary strategy. As fires rage across a landscape, aided by dry cheatgrass, they kill native competitors, allowing cheatgrass to spread even further.

It’s been a problem for ranchers, wildlife biologists, and land managers for decades, but until recently, few studies had explicitly shown at what point mule deer will simply avoid cheatgrass-covered areas.

UW professors Jerod Merkle and Brian Mealor, along with research scientist Kurt Smith, used data provided by Western EcoSystems Technology biologist Hall Sawyer to examine how mule deer behaved in much of the state’s northeast corner.

The researchers observed deer collar points moving into and out of areas with good food and habitat, while avoiding areas with increasing amounts of cheatgrass.

Jill Randall, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department’s big game migration coordinator who was not involved in the study, said the findings make sense.

“Deer are super selective foragers, and if they can choose between native and non-native, they will go where there’s something better,” she told me. “If cheatgrass is scattered among things, they will nibble, but 20% or higher is fairly dominant. If they have the opportunity to eat other native species, they will.

The problem arises when the deer run out of other places to go.

Hope for conservation

A study published in August used camera traps to demonstrate that mule deer will return to areas with native plants after cheatgrass is removed.

That is also what Smith, Merkle, and Mealor’s models demonstrated. Mule deer will return in abundance after cheatgrass-covered acres are treated, potentially reversing much of the 50% habitat loss that would otherwise have occurred.

According to the authors, the purpose of the paper is not to cause alarm, but rather to explain the gravity of the situation and the possibility of solutions.

Gov. Mark Gordon and state lawmakers agree, and earlier this year awarded tens of millions of dollars in grants and loans to combat invasive grasses.

Bottom line, Smith stated, “If we do nothing, we’re in trouble. “But there is hope.”